There’s No Such Thing As A Free Lunch

The Economics of Your Energy, Why Nothing Is Free, and How to Calculate the Real Cost of Anything.

I’m sitting in a large study hall my freshman year, about four weeks into college. As an honors student, I was required to attend a freshman seminar where, each week, a different professor would pitch us on why we should study their discipline.

One week it was intersectional feminism. Another week, the history of mass communication. And then came the economist.

She marched into the room with a confidence only a lifelong academic can pull off and announced, “I’m here to teach you the coolest new acronym you should start using.”

This was in the height of lol, brb, ttyl culture, so when she wrote the world’s longest acronym across the board, TINSTAFEL, I laughed out loud. There was absolutely no universe where I was using that in a text message.

But then she explained it:

There Is No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

At first, I rejected it. I had literally eaten a free lunch earlier that day. But then she kept going.

Economics, she said, is the study of how we make tradeoffs, money, resources, time, effort, desire, on both the supply and demand side. Everything has a cost. Everything requires sacrifice. Every choice creates ripple effects.

When her lecture ended, she told us, “If you forget everything else, remember TINSTAFEL.”

And oddly enough, I did. Not because I wanted to, but because once you hear it, you start seeing it everywhere…

Where TINSTAFEL First Showed Up

The first place I noticed it was on campus. College is full of “free”: free T-shirts, free sunglasses, free cups, free frisbees, free flip-flops, and of course, free food. There was always someone handing out “free.”

But I’m Type A. I crave clean, minimal, intentional spaces. And after that seminar, I realized all these “free” things weren’t actually free.

They cost me my peace: The “free” clothes cluttered my tiny dorm. The “free” cups filled cabinets I wanted clear. The “free” pizza cost me energy and nutrition, as a college athlete who needed real food. Nothing was free if it disrupted the life I wanted to live or the person I was trying to become.

That was the first time I realized: Cheap can be very expensive. And “free” can come with the highest price tag of all.

Where It Really Landed: Investment as More Than Money

The second time TINSTAFEL hit me hard was when I was making my first angel investment.

I approached a mentor I deeply respect, someone whose brain I wanted to borrow. I told him about the opportunity and asked for his perspective. He listened carefully and then said something I’ll never forget:

“You’re assuming the only thing you’re investing is money. But you bring far more than that to a company. If you treat this as just a check, that’s all it will ever be. But if you treat yourself as part of the value, the return becomes bigger than the money.”

He asked me what I thought I brought to the table. I told him: storytelling, pitching, connections, vision, the ability to help the founder take the elevator instead of the stairs.

He nodded. “Exactly. You’re not just writing a check, you’re writing yourself into the equation.”

Then he said something that has shaped every investment decision I’ve made since:

“Over time, you learn that the return in an investment like this isn’t just financial. It’s knowledge, networks, opportunity, and those things compound in ways you can’t predict.”

And there it was again: TINSTAFEL. Even when something isn’t free, the true cost, and maybe more importantly, the true return, is always broader than dollars.

When It Got Personal: The House That Cost Too Much

The most recent, and maybe the most emotional, example of TINSTAFEL came when Ronnie and I decided to sell the home I thought would be our forever home: our dreamy A-frame.

When I first saw it, I saw our whole future: long summer pool days, nights roasting s’mores, winters ice skating on the pond, marshmallow-topped hot chocolate cheers from a rink-side igloo. It was magic.

But turning that house into a home that matched our family’s needs and energy? That would require a renovation so major it felt like taking on a second full-time job.

The actual cost wasn’t just money. It was our life, our harmony, our bandwidth, our peace.

A renovation like that would cost us years of weekends in the form of memories not made. The life it would take from us was greater than the life it would give us, and that was a hard truth to reckon with.

So we sold it. And while I was emotional (some might have called me a sob-kabob at the time), it was the right decision. Because the only thing I wanted more than that house was our life.

The Real Lesson of TINSTAFEL: The Economics of Your Energy

The older I get, the more TINSTAFEL feels less like an economic principle and more like a life principle.Everything has a cost.

So the real question becomes:

What is this actually costing me? And what am I getting in return?

This led me to a simple but powerful framework I now use for almost every decision.

How to Calculate the Real Cost of Anything

You can use this with purchases, opportunities, relationships, commitments, habits — everything.

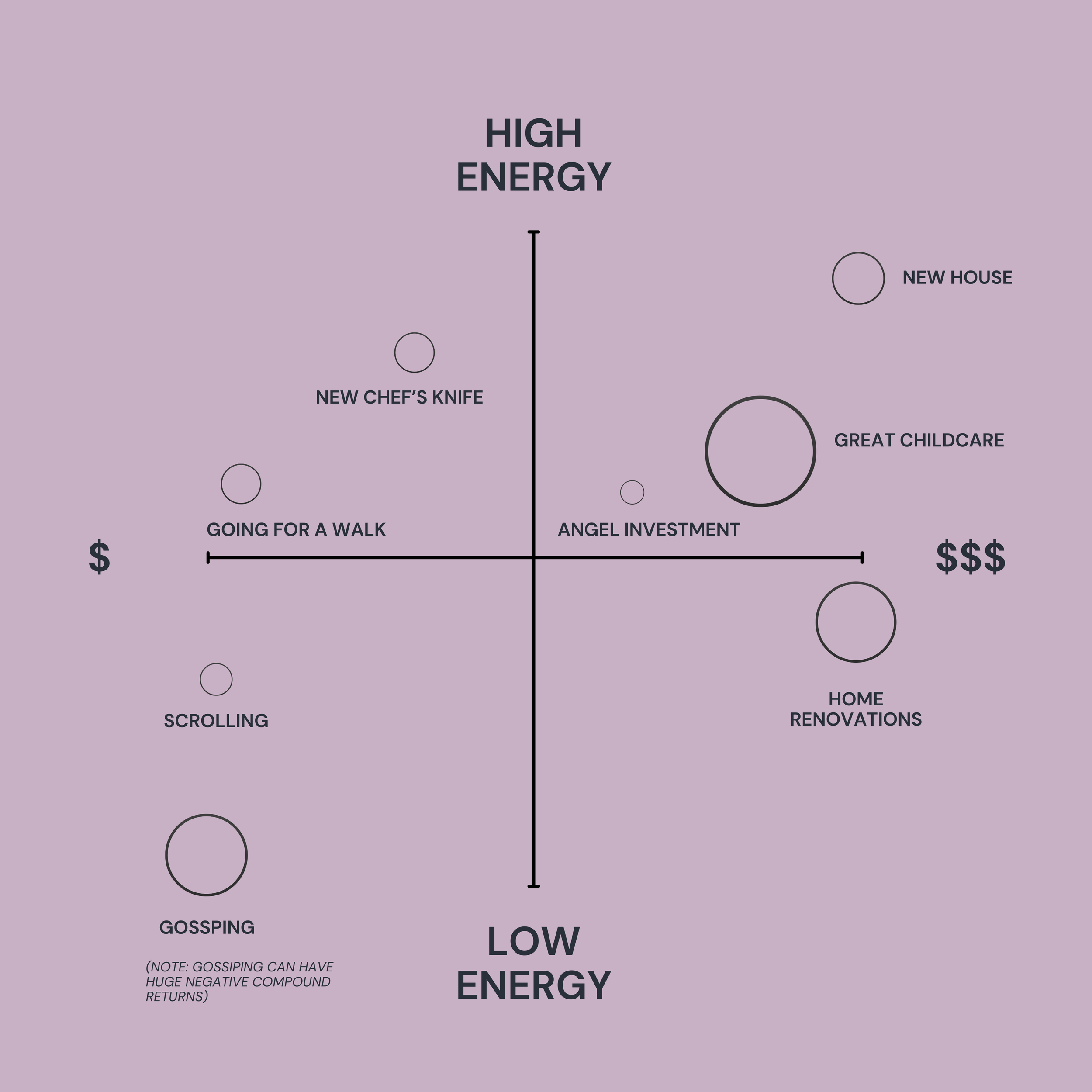

There are three levers:

1. The Dollar Expense (X-axis)

How much money does this require?

(Is that money well spent?)

2. The Energy Payoff (Y-axis)

Does this thing drain, restore, or expand my energy? Does it make my life heavier or lighter?

3. The Compounding Multiplier (Bubble size)

Does this continue paying dividends over time: in clarity, freedom, joy, opportunity, connections, confidence, identity?

These create four quadrants:

The Four Quadrants of Energy Economics

Quadrant 1: High Cost, High Payoff — “The Power Investment”

This is the angel investment. The house. The car that keeps your family safe. Childcare. Therapy. Delegation.

Yes, the ticket price may seem high at first glance, but the returns compound for years, often in ways you can’t predict in the present. This is where you want to invest.

Quadrant 2: Low Cost, High Payoff — “The Sweet Spot”

Small rituals that bring you joy. Saying “no” early. A kitchen reset. A boundary. A walk. A candle. A 10-minute tidy.

Low cost, huge return. Stack as many of these as you can.

Quadrant 3: Low Cost, Low Payoff — “The Neutral Zone”

This is where things like Free T-shirts and free lunches fall. But also things like scrolling, busy work, and comfort entertainment.

They’re not harmful in small doses, but they’re also not life-giving. Here, you need to stay consciously aware of when these hit the point of diminishing returns.

Invest in these sparingly.

Quadrant 4: High Cost, Low Payoff — “The Burnout Trap”

Doing it all yourself. Overscheduling. Overgiving. Staying in things out of obligation. Renovations (actual or theoretical) you don’t actually want to live through. Huge energy drains, little (and sometimes negative) returns.

My best advice: stay out of this quadrant as much as possible.

And look, I’m a realist and I know that won’t always be possible. For example: if someone you love loses a loved one, showing up for them may cost you a ton with no immediate payoff, and in fact it may drain you big time (in time spent with them, dollars spent catering food for them, and emotional energy helping them get through a tough time, etc) to be there for them. But the compounding effect of showing up in a meaningful way for that person today will certainly bloom into something beautiful over time when it’s your turn to receive.

Just know that too much in this quadrant creates a heavy life. Be wary of investments that fall here, and don’t martyr yourself under the weight of high-cost, low-payoff decisions.

The Bottom Line

As much as I thought TINSTAFEL was about money and lunch, it’s actually not about either.

TINSTAFEL is about the economics of your energy.

When you optimize your life for the top two quadrants, the investments and the sweet spots, your life expands, your energy expands, and your overall satisfaction expands.

When you drift into the bottom right too often, your life contracts. Your energy depletes. You get crushed by the weight of decisions that may have “cost you nothing.”

Everything costs something. The question isn’t whether or not you can afford it, it’s whether or not you want to.

Is the life you're building worth the price you're paying?